In the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, urban space in the Twin Cities was transformed by graffiti and street art, including words and images expressing a wide range of emotions, demands, and visions for the future. Urban Art Mapping, the interdisciplinary research team that we co-direct, seeks to document, archive, and analyze graffiti and images in the street. These images are created as a form of protest in response to the violent horror of police brutality and systemic racism in all of its forms around the world. Street art activates space in a special way, calling us to stop and consider the spaces through which we move and exist in a new manner. We argue that graffiti and street art represent a multitude of community voices, providing a counter-institutional narrative that demands immediate attention. The narrative of the uprising and its demands for societal transformation are ongoing and complex, and they are written, drawn, and painted on plywood panels and walls in public spaces.

The art we’ve documented that sprung up following the uprising serves as both a memorial to George Floyd and a call for justice and equality. One of the first things members of our team noticed in the days following the uprising was the way public space had been transformed by the appearance of new street art. For BIPOC members of our team, public space in the city could feel exclusionary. The majority of the buildings have been designed by White people for White people; commercial buildings act as monuments to a system that has exploited and excluded BIPOC folks for centuries. Signs and signals reference a set of laws rooted in a system of control of BIPOC bodies, making sure they stay in certain areas of the city, move only in certain ways, and defer to authority. Those spaces are now blanketed with street art—posts, walls, traffic signs, sidewalks, and building facades— providing a new space to express the pain that many of us felt, the trauma the community was experiencing, and a collective resistance. It was, for us, as if the city had become a memorial not just to George Floyd, but to his experience as a Black man in a world that didn’t value him as a human being. In this way, street art – sanctioned and non-sanctioned – was not criminal or destructive. It was an expression of refusal and a collective community response to injustice.

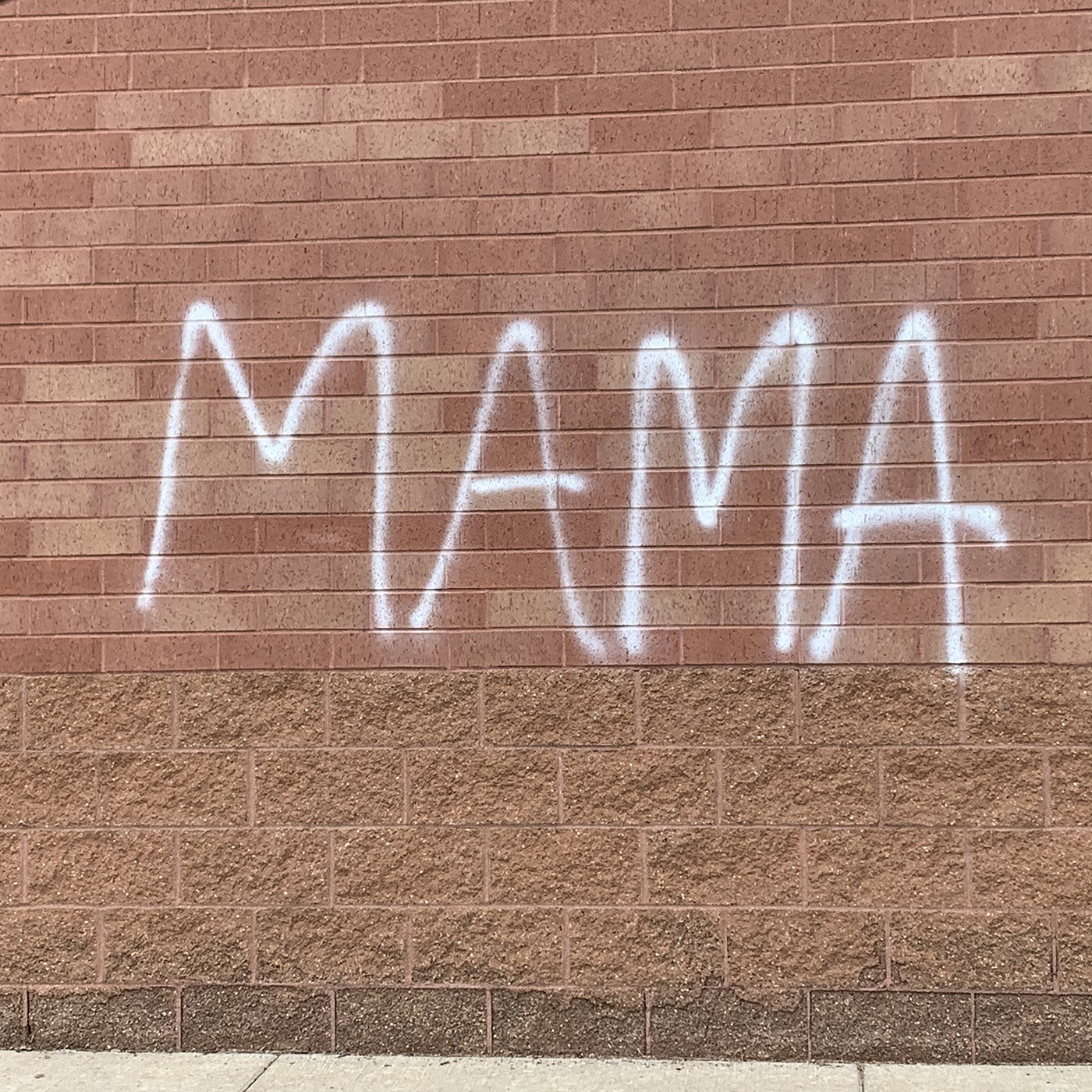

At the height of the uprising, we photographed "Mama," a simple text spray-painted very quickly by a protestor on a wall of the former Walmart. Because of local restrictions and attitudes towards graffiti, and because it was created as part of protest that was heavily suppressed, we knew that this piece of graffiti was destined to be erased quickly, and we recognized the need to document it. "Mama” expressed a raw response that came from the community and represented a shared voice, but the process of painting spontaneously on a wall did not require consensus, as a traditional monument might. In the days that followed, paintings went up on plywood panels adding new layers to the conversation. Now, well over a year later, protest art in the form of stickers, stencils, murals, posters, sculptures, and installations continues to make demands for justice and equality throughout the Twin Cities and around the world, often concentrated at sites of conflict.

Our intention is for the George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art Database to serve as a resource for anti-racist research, teaching, and action. The project is crowd-sourced. While this decision is a practical one, as the scope of the archive is global and our team cannot be everywhere at all times, crowd sourcing also destabilizes the authority of the archive by inviting communities to participate in the process of documentation. The images are carefully contextualized by way of metadata that includes a description, identification of key themes, geolocations, and dates of documentation. To this end, the project facilitates an analysis of the texts, iconography, and issues that appear in protest art, explored in relation to local experiences.

The production of street art is quick and immediate in contrast to the slow and meticulous process often involved in creating traditional memorials. It is also intentionally ephemeral. The visual narrative created through protest art in the streets is in a state of constant change, as new conversations and dialogues emerge over time. We invite contributions to the George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art Database, including images from the summer of 2020 as well as more recent examples of graffiti and street art, using this link.

Mama written in white spray paint on the wall of a former Walmart on University Avenue in Saint Paul. Photographed on June 2, 2020. This was produced in the context of intense conflict between protestors and police along Saint Paul’s University Avenue on May 28, a week after the murder of George Floyd.

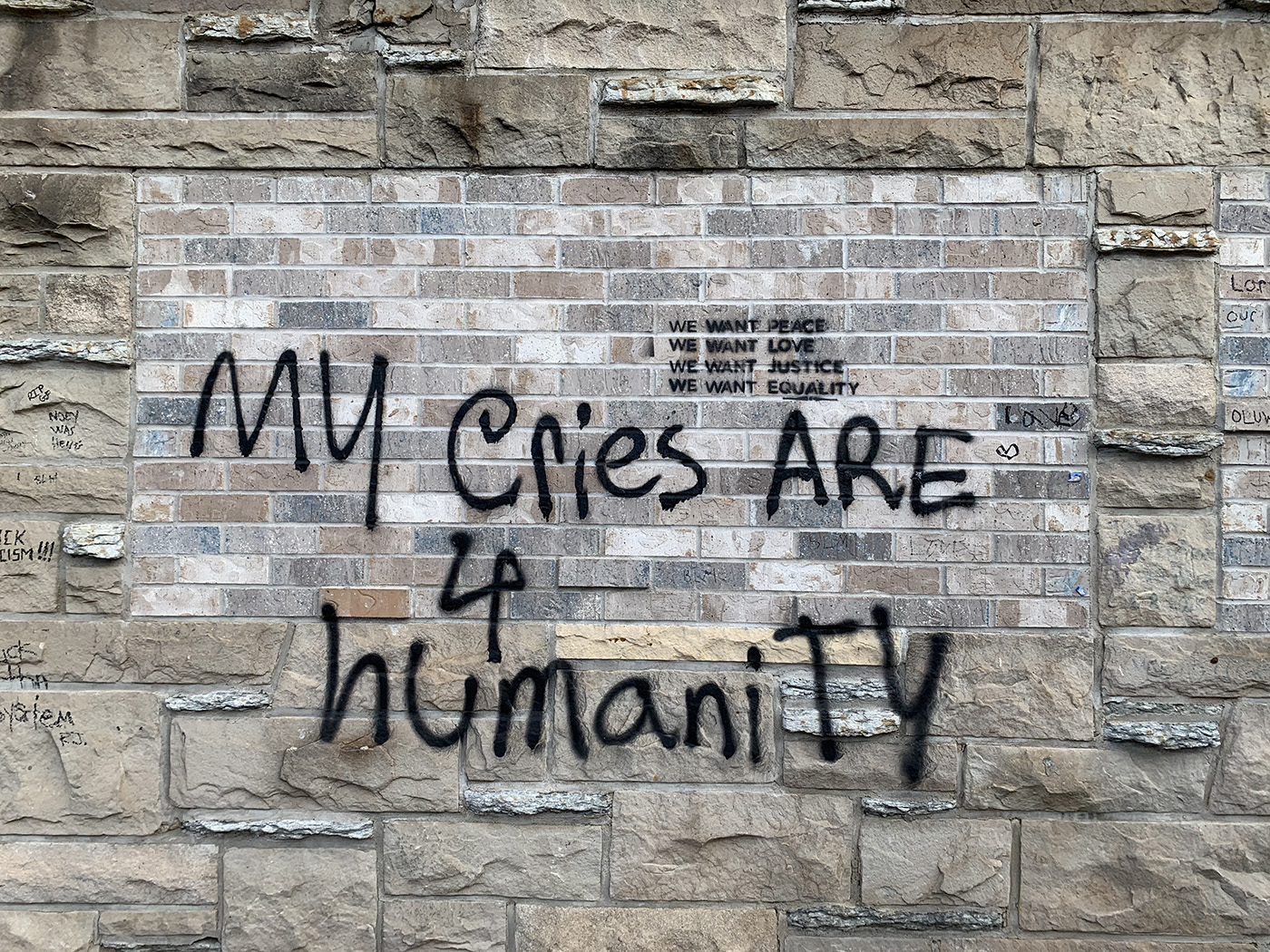

Graffiti on a wall near the site where George Floyd was murdered, photographed on October 16, 2020. This is an example of graffiti that was painted quite quickly and could potentially be very temporary. However, the writer selected a surface that would make it difficult to remove, and graffiti has been tolerated at 38th and Chicago.

Anna Barber and Connor Wright, Say Their Names Cemetery, 37th Street and Park Avenue, Minneapolis. Installed June 5, 2020, photographed on October 16, 2020. This installation was created by two artists who traveled to the Twin Cities from out of state and it is located about two blocks from where George Floyd was murdered. This symbolic cemetery includes grave markers to honor BIPOC lives lost through acts of racial violence.

Simone Alexa, Make Space for Healing and Grief, Photographed April 24, 2021. This image of a joyous BIPOC gathering in the forest was painted in the aftermath of the killing of Daunte Wright in nearby Brooklyn Center on April 11, 2021, and at the time of Derek Chauvin’s trial. Tensions were high in the Twin Cities during this period of time, and many storefronts covered their windows with plywood again. However, the specific space where this mural was located was not an active site for protest at the time when the work was produced, and the message calling for healing and grief reflects the need for art that can play a therapeutic role in the community.

This piece was painted on plywood on the side of a building on University Avenue, a major pathway connecting Minneapolis and Saint Paul. The words “Unlock Cages” are written in large black letters in front of a snapping chain and a chain link fence. There is a vivid green nature scene behind the text and chains. The phrases “Education Not Incarceration,” “People Before Profit,” and “Black Lives Matter” are also written below to further emphasize the artist’s disdain for inequality. This was painted in late May 2020, but it is still installed in this space.

This essay in the “Changing Monument Landscape” series was commissioned as part of the launch for the National Monument Audit, produced by Monument Lab in partnership with The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more on the Audit, visit monumentab.com/audit.