Between August 2020 and May 2021, artist Young Joon Kwak held the position of Artist-in-Residence in Critical Race Studies at Michigan State University (MSU) in East Lansing, Michigan. In this position, Kwak was to teach courses in the Department of Art, Art History, and Design and collaborate with the campus community in order to produce a public art project engaging issues of race, gender, diversity, and inclusion. At a time when so few bodies were present on campus due to the global COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home orders, Kwak turned their attention to the university’s famed bronze statue of “The Spartan,” the exemplary body of campus pride.This statue, cast from the terracotta original sculpted in 1945 by Leonard Jungwirth, a professor of art at MSU from 1940 to 1963, currently stands on the northwest corner of campus. It was installed and unveiled in 2005. Kwak recast it for their exhibition of sculptures and prints at MSU’s Union Gallery this past spring (the show will be represented with additional new artworks this fall at Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles).

Below, Kwak and Jeanne Dreskin, Monument Lab’s Writer-in-Residence, have collaboratively assembled an exchange between Kwak, who speaks from their own perspective, and an imagined voice that speaks from a subject position embedded within the MSU community. The voice’s rhetoric reveals a series of institutionally codified beliefs, traditions, and myths that Kwak found to be heavily concentrated in and around the Sparty statue. Kwak’s statements contest these predominant understandings of Sparty, reflecting the personal impressions, encounters, and confrontations that fundamentally shaped their residency experience and the exhibition that came from it.

Voice from MSU: MSU’s Sparty statue is iconic. It exudes a majestic aura that’s both unmissable and unforgettable. It’s the main attraction on campus and the requisite backdrop for photos celebrating every student milestone. Guided tours, family weekends, rivalry weeks, graduations, and alumni reunions are all incomplete if not commemorated by a visit to Sparty. Proximity to, reverence for, and exaltation of the statue all authenticate the MSU experience. To be pictured with the statue is to confirm that in this place, one is undeniably a “true Spartan.”

Standing approximately fifteen feet high, Sparty serves as the capstone of Demonstration Field. It can be spotted from hundreds of yards away, perched on a massive five-foot pedestal that mimics a tri-level winner’s podium. It presides over a nexus of converging footpaths, staged centrally on a circular, raised brick platform and framed by a low retaining wall. Step onto the platform and you’re in the presence of a giant. The closer you get, the more you have to crane your neck to take it in. Sparty looms so large—both literally and figuratively—over campus life that its claims to space are exceeded only by its symbolic claims to time. It is indelibly intertwined in MSU’s history, present, and its future legacies.

Young Joon Kwak: When I began researching MSU after applying for the Artist-in-Residence in Critical Race Studies position, I found that the Spartan statue and symbol was inseparable from the identity of the university. I got the job early on in the pandemic, at which point I saw a news item about how the university placed a large face mask on the statue to promote mask-wearing on and around campus. To me, this demonstrated how the symbol of the Spartan has been cultivated by the institution in ways that carry so much weight, influence, and power over the community.

At the time, I was inspired by burgeoning public debates around monuments in public spaces and institutions, which were developing alongside the country’s growing political movements and social unrest. I wanted an alternative and more complex form of engagement. Rather than simply politicizing the symbol of the Spartan in a polarizing way or seeking to demolish it, as has been done with so many other statues and monuments around the world, how could I connect with Sparty as a means of connecting with the community?

When I first saw the statue in person, it felt so high up, so untouchable, impenetrable. It’s up there, I am down here. It’s so huge, I am so small. It’s so hard compared to my soft, squishy body. It’s so proud, so White. I saw how much people identify with it, adopt it as a form of representation of the community—or it adopts the community. But not me, and not many others, it turns out. I wanted to look at it closer, to see it on its level. The pedestal was pushing me away from it, enforcing distance. At the time, the pandemic was compounding heightened social and ideological rifts across the country. Being in isolation in this swing state during a presidential election year, all I wanted was touch, intimacy, to understand.

Voice: To know Sparty is to understand its crucial role as the MSU community’s great connector. For those lucky enough to have made memories at MSU, the mere sight or mention of Sparty no doubt recalls their happiest times on campus. Standing next to the statue, perceiving its magnitude, feeling parts of its bronze skin...these experiences can be transportative. They offer a portal to MSU’s institutional past.

Sparty represents the social bonds that community members share with each other, as well as the characteristics that every Spartan can take pride in sharing with the world. It pronounces to every student, faculty, and staff member, “you are welcome here, and you belong.” As long as Sparty stands, it will stand firm for Spartan ideals, inspiring everyone in the community to do the same. In each of these ways, Sparty is alive. The statue’s body exudes a palpable, vibrant energy that permeates the space around it. To be amidst the statue, especially with fellow Spartans, is to feel and participate in that energy, like rising to cheer in a crowd of fans at a championship football game.

Sparta was one of ancient Greece’s most successful military states and its citizens prized physical fitness, strength training, and readiness for battle. Sparty’s taut, angular form is a testament to this legendary might and fortitude. From its square jaw and broad shoulders to its strikingly defined abdominals, sinewy legs, and confident pose, the statue evokes a consummate warrior. It holds its head aloft, unafraid, while drawing its helmet down to its side. The softness of its flowing drapery complements the firmness of its stance and the steadiness of its gaze. It embodies the tenacity, conviction and humility of great Spartan athletes and their supporters—poised, sportsmanlike, and primed for greatness. Sparty’s is a body that aspires to invincibility.

YJK: In my research, I came across a Reddit thread that discussed a petition to replace the Spartan statue with another version of the Spartan, Fernando Botero’s Il Guerriero (1992). This indicated that there was a contingent of people who felt that the current representation of Sparty on campus was outdated in its essentialized ideals of raced, gendered physical fitness, and how this can bolster real harmful effects of objectification, shaming, and violence enacted on differently abled/non-normative bodies.

Icons and exemplary bodies like Sparty’s are mechanisms for the workings of power through discourse. They invoke an identification that can objectify or subjugate the viewer. What if the exemplary body of ideal physical fitness was one of fluidity, formlessness, and fragmentation? I can’t help but imagine possibilities for an icon that represents a newly radical form of consumption and identification. What, then, would become of identifications of beauty, gender, race?

To me, Sparty symbolizes whiteness. It’s a symbol that is so entangled with White supremacy as to be inseparable from it. It’s similar to how western civilization has become a euphemism for White civilization, which forgets that ancient Greeks and Romans didn’t even consider themselves White. The institutions that use Spartan imagery and other classical symbols blindly and without any critical reflection play a role in constructing and upholding whiteness. They continue to exclude those who have felt voiceless or invisible, those who’ve never seen themselves duly represented or are often misrepresented. It excludes the experiences of many trans, disabled, and non-normative bodies, those of us who recognize our bodies as sites of contradiction within the western/patriarchal/White male gaze. It excludes the complexity, the nuances of all our bodies, our selves, and our identities that can’t be captured by that gaze.

I’m less interested in “equitable” representations of different human bodies that are already known and recognizable than I am in forms that are bodily yet beyond what we think of as human bodies—beyond the skin.

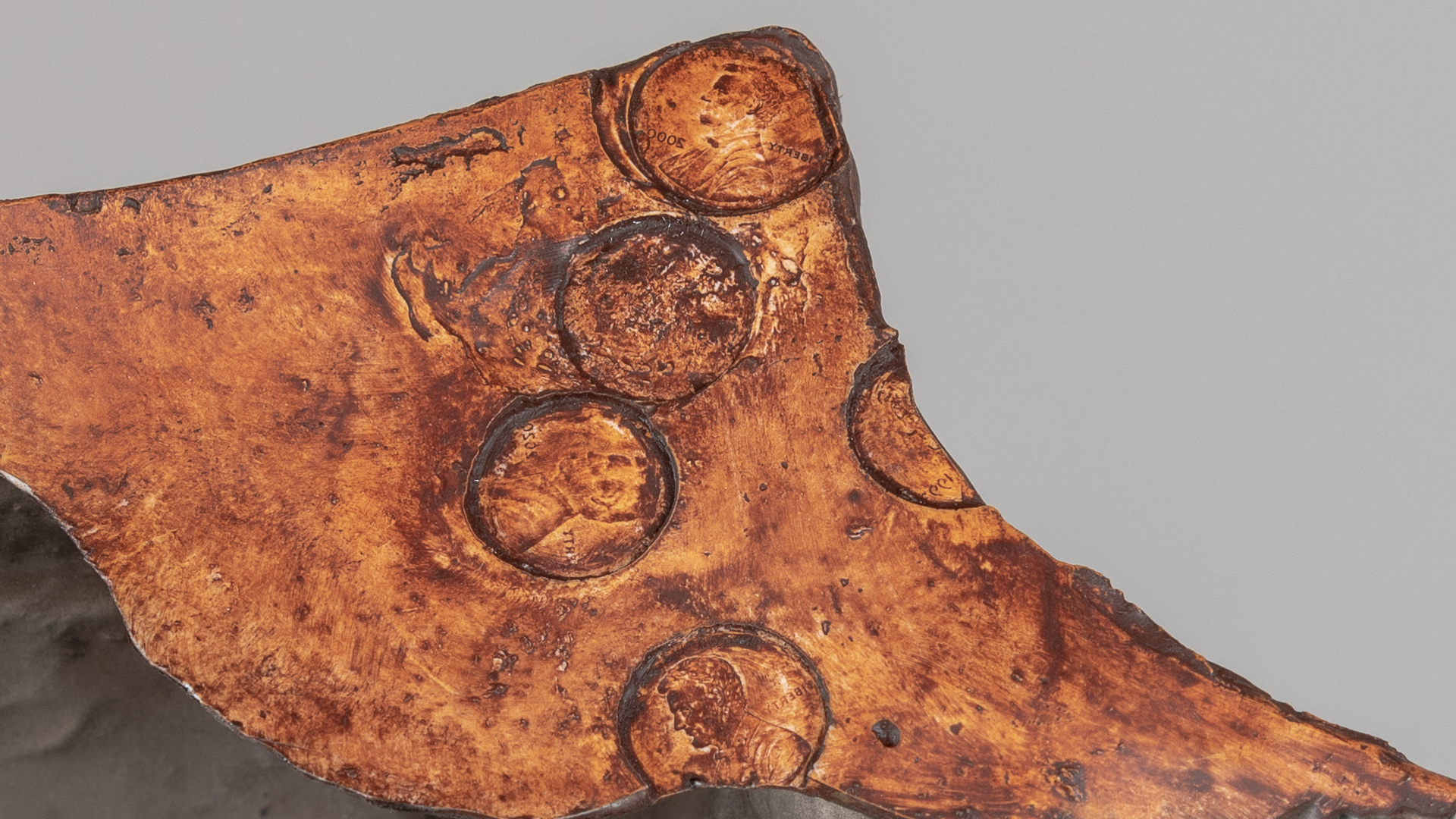

Voice: Sparty exists to be both seen and touched. The statue tends to receive a kind of collective veneration reminiscent of religious idols: it’s a necessary stop on the Spartan Walk, the football team’s traditional fifteen-minute procession from the Kellogg Center to the stadium locker room prior to every home game. When players and coaches reach the statue, most place or toss pennies at its feet, which is believed to bring the team auspiciousness and, hopefully, a Spartan victory. Some pause briefly to graze their hand across a part of Sparty’s bronzed surface, letting their touch linger. Some have even left pennies on Sparty permanently, adhering them to its toes or in recesses of its body. In these moments, Spartans’ personal connections to the statue and the communal spirit it inspires become tangible. When MSU shows the statue its Spartan pride, the statue is known to return the favor.

YJK: I imagine each touch of the statue, each penny placed on its body by the players, coaches, and fans, as being loaded with individual and collective hopes, dreams, and prayers. I also think of Jungwirth’s touch in modeling the original statue—the varying pressures and sheer multitude of his hands, the care and tenderness with which he modeled this exemplary body, his years of training and artmaking culminating in the creation of this monument. All this reveals the human construction of this symbol, and with it, the potential for its reconstruction. Perhaps Sparty can be a site for imagining a sort of material transformation, creative agency, and unfixed potentiality.

Voice: In 1925, Michigan Agricultural College, the first agricultural college in the United States, became Michigan State College (MSC). This name change officially recognized the college’s newly expanded curriculum, which had designated a degree-granting division for liberal arts alongside that for agriculture and engineering. It was also at this time that the college’s athletic teams, previously known as the “Aggies,” briefly became the “Michigan Staters,” then finally the “Spartans.” This is the name which we have come to know and love, which inspires pride in our community members, and which has brought such immense renown to MSU athletics. Seven years later, MSC Athletic Director Ralph Young encountered the University of Southern California’s bronze “Tommy Trojan” statue, which had been unveiled in 1930 as a gesture honoring USC’s own athletic prowess and university culture. Young was inspired to suggest that a similar statue be built of the Spartan at MSC.

The Spartan not only represents the history and enduring spirit of MSU, it honors the university’s connections to ideals of the classical past. These ideals, born in civilizations of antiquity, gave rise to the foundational American concepts of sovereignty, democracy, liberty, and humanistic education that have shaped our academic and political institutions.

YJK: As an artist and teacher, I want to expose these hegemonic associations and untruths from within by working with the institution’s platform and resources as they currently exist. I want to not just rethink past narratives, but also reflect on who we are today and where we are going.

I’m not interested in replacing or demolishing a symbol for demolition’s sake. I want to build something. My work is not about the negation of the Spartan symbol, but a twisting of it, setting it into motion, allowing it to resignify in ways that carry multiple meanings and allow for new interpretations and forms of interaction.

Voice: As one of the university’s most present and significant symbols, the Sparty statue is accorded the utmost respect. As a bestower of luck to Spartan athletes (especially football players), the statue achieves a level of sacredness. This quality extends well beyond offerings of pennies and hopeful, lingering touches on its skin. Community efforts to protect and maintain the statue are simultaneously efforts to protect the virtue and integrity for which the statue stands. Therefore, caring for Sparty—keeping it clean and free from harm—is paramount.

Sparty Watch, a group of students, alums, and fans who volunteer to stand guard at the statue to protect it from vandalism (especially during Michigan-Michigan State rivalry week), arose out of the agreed upon need to maintain Sparty’s protection. All Spartans take Sparty’s welfare seriously, but members of Sparty Watch take it just a little more seriously. It’s an honor, after all, to show up for Sparty and to defend what the statue means to each of us.

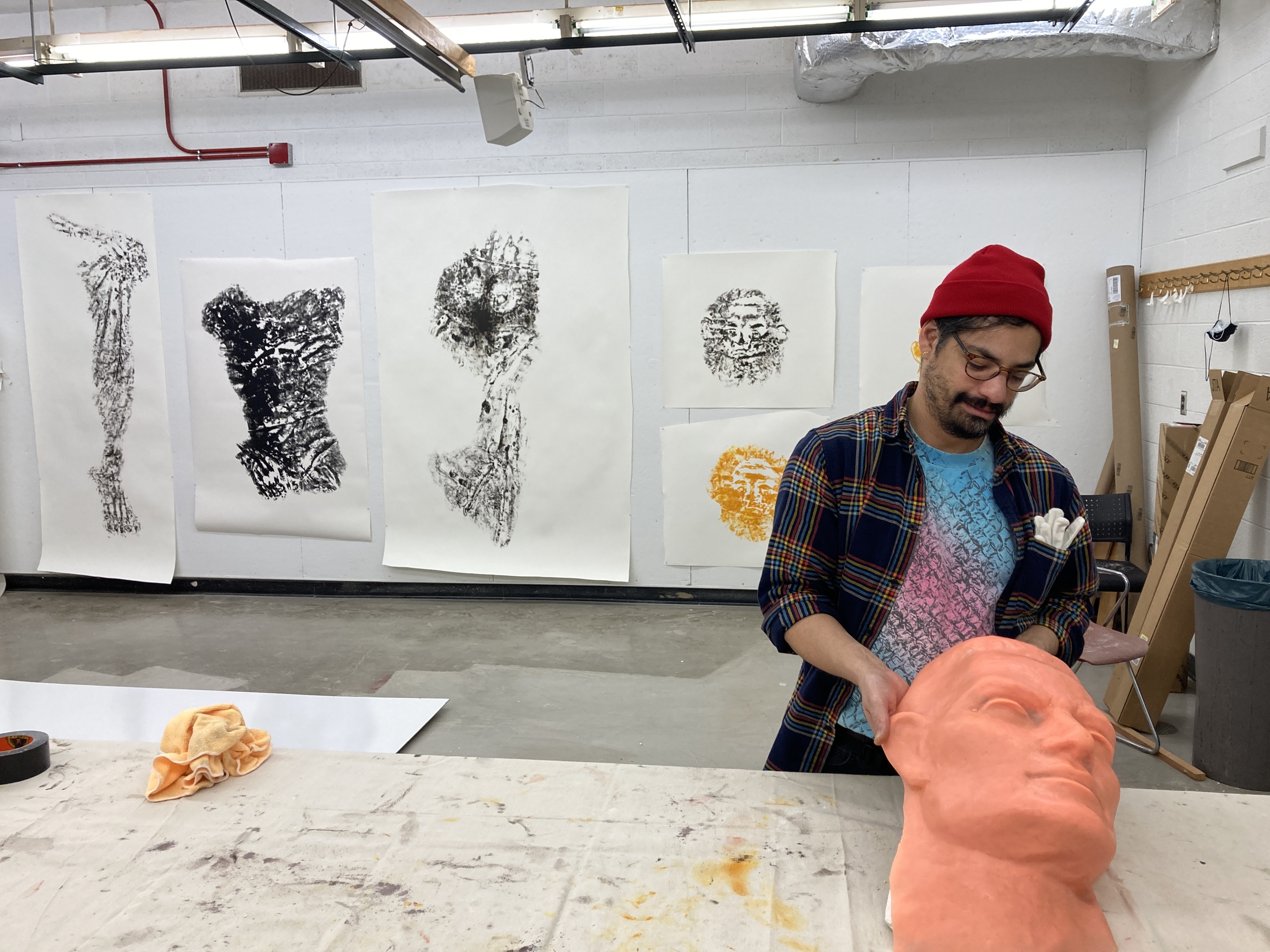

YJK: During the on-site mold-making process at the statue, my assistants (Lauren Batdorff and Nicolei Gupit) and I gently brushed silicone all over Sparty’s body, tracing the motions of Jungwirth’s hand. I tried to imagine a bit more about his subjectivity, and how it informed his decisions to make Sparty’s ass (and other body parts) in just this way. The silicone is fluid, amorphous, and goopy. It reflected for me how identifications can be inscribed into gestures, as well as how gestures can be inscribed into materials. Drenched in silicone, Sparty reveals itself as a set of not-yet-formed definitions. It connotes a sense of breaking free, a continual realization of becoming, or of never having arrived.

There was a physical barrier and sign explaining the project along the perimeter of the statue site while we were working. Some people just hopped over it, disrupting our process that involved time-sensitive materials (curing of plaster and silicone). I was surprised by how wild some people’s reactions were and how many of them jumped to the conclusion that we were vandalizing or harming the statue, to which they took great offense. People would read the sign explaining the project and yell out things like, “what the fuck is critical race studies,” showing aggressive disdain for the concept. Or maybe they were just aggressively confused. Some people implicitly politicized the work and demanded that we tell them who we were voting for (it didn’t help that this process took place during election week).

We tried our best to meet this hypermasculine aggressive energy with patience and politeness, though some people were unrelenting and refused to believe the project’s intentions. I questioned whether the project was worth putting my assistants at risk of violence or abuse, terrified that some unmasked screamer would give one of us Covid or that some confrontation would escalate. Was it because my assistants and I, as femme/genderqueer artists of color, looked different?

Multiple people called the city police (who had been notified about my project), or threatened to call them. A guy named Johnny Spirit showed up unmasked on the first day that we were working and immediately started getting in our faces and breaking social distancing rules. He harassed us with questions while recording us with a camera. Supposedly a member of Sparty Watch, he set up wireless cameras to surveil us and continually walked around the site, at one point even climbing the scaffolding to record us working. Every so often, one of his fellow Sparty defenders would show up and join him in interrogating us. Johnny Spirit stayed with us throughout the entire first day of working on site. When he showed up the second day, the campus police had to ask him to leave and gave him a warning, which provided us with some relief.

While there were these moments when I wanted to hide, we also had conversations with passersby who were intrigued, or at least open, to the project and its intentions. They shared their own personal stories and myths and anecdotes about the statue. All of the attention, curiosity, and concern around Sparty heightened my own awareness of the community’s intense attachment, sensitivity, and identification with it and with the symbol of the Spartan in general. This confirmed for me that I’d chosen the appropriate subject matter for a project meant to engage the campus community. It also confirmed for me that I’d made the right decision to not wear my already-purchased Spartan cheerleader drags for the occasion.

Voice: By the late 1980s, Jungwirth’s original terracotta statue was over four decades old and in dire need of repair. Weather and sandblasting for graffiti removal had caused the sculpture to warp and crack. A “Save our Sparty” committee was formed to raise funds for a renovation. Despite the renovation’s successful completion, by the early 2000s it became clear that Jungwirth’s terracotta work would simply not outlast the elements. The new cast was produced, the original was relocated to MSU’s Spartan Stadium, and the now-famous bronze Sparty was installed in its current location. With this casting, Sparty was given a new lease on life. It became whole again, projecting an enduring, indestructible quality befitting of the Spartan image.

The statue’s 1,500-pound bronzed physique, like the MSU spirit, is sturdy and resilient. This sense of durability rightfully looks to the future, promoting an everlasting legacy for not just the statue itself, but for the values it has come to represent.

YJK: For the presentation of my project at the MSU Union Gallery in Spring 2021, I created sculptural “skins” and print-based “impressions” of the statue. Rather than creating a replica of the statue by using the mold as a [negative] vessel to create the [positive] art object, we cast the molds themselves, using the negative as the positive. The resulting artworks were deconstructed reverse casts of Sparty’s body. Like trace fossils, these acts of “skinning” Sparty reveal new details through its body’s absence, newly animating the physical and social life of the Spartan. These skins and impressions suggest a multiplicity of possible truths about the life, evolution, and history of a bygone being or thing. They inspire critical inquiry and imagination in those who observe them. They can be sites of indeterminacy and of queerness.

I want to invite people to question what lies beyond the symbolic skin of the Spartan. The sculptures’ concave surfaces are burnished with wax and pigments, which highlight the marks originally made by Jungwirth, the little details on the surface of the statue that otherwise go unnoticed, and the scars that have accumulated over countless interactions with humans in the statue’s environment. Traces of Sparty remain in these skins, but they reveal new marks, forms, shadows and gestures that could lead to newly reimagined bodies and futures.

The skins are presented in fragments. As sculptures, they create opportunities for new and multiple viewer projections and reflections. Their scale and viewing height bring them downward, closer to our own bodies. Sparty is now on our level and we may look closer, longer, and from different angles. The larger floor sculptures (torso and groin) are installed to be viewed horizontally. They reveal a quasi-corporeal or carnal topography that maps bodily potential beyond the limits of the skin. Sparty becomes a site of emergence and immanence. A new body being found.

The works on the wall (the “impressions”) are monoprints made from silicone casts of Sparty that I inked using a cosmetic application technique, with body makeup sponges. The scale of the prints is more monumental than that of the sculptures, but they immerse viewers in something that appears short of a clear image, where distinctions between figure and ground are porous. Their open chasms and critical gaps make space for viewers to project, imagine, and connect Sparty with other forms, concepts, or narratives, which can all become new growths. One can imagine the affective flows moving in and out of these chasms, creating potential for unforeseen interactions in between fragments.

These impressions don’t occupy a singular space of figuration or abstraction, symbol or gesture. They can be thought of as spaces of indeterminacy or unfixed potentiality, inviting viewers to expand their preconceived notions of Sparty’s exemplary body. Normative identifications of race, class, gender, and their attendant divisive politics blur while transformation and movement unfold in their place. In these spaces, the touch of Jungwirth’s hand, my hand, and the viewers can all join to build something new.