Monuments offer interpretations of the past and play an outsize role in shaping historical narratives and shared memory. In the service of remembering the preferred narratives of their creators, they also can erase, deny, or belittle the historical experience of those who have not had the civic power or privilege to build them. Where inequalities and injustices exist, monuments often perpetuate them.

Monument makers often strive for surface-level markers of historical accuracy, paying close attention to authentic details of clothing, weaponry, and quotation, but often eclipse social factors that inform public memory and broader contexts. This includes elevating figures as singular, without the people who made their contributions possible, or situating them in places they never set foot. Monuments suppress far more than they summon us to remember; they are not mere facts on a pedestal.

Some monuments are obvious fabrications. Several monuments put historical figures together in unlikely combinations. For example, in Camden, New Jersey, America Receiving the Gift of the Nations (Nicola D’Ascenzo Studios, 1916) depicts the United States, embodied by an otherwise nondescript white woman, receiving contributions from Moses, Renaissance painters, Christopher Columbus, William Penn, Johannes Gutenberg, Walt Whitman, and Dante. In Washington, DC’s Emancipation Memorial (Thomas Ball, 1876), President Abraham Lincoln is depicted alongside a fugitive enslaved man named Archer Alexander whom he never met, saw, or freed. Our Top 50 list includes historical figures such as Nathan Hale and Sacagawea, whose actual likenesses are largely unknown and whose biographies are unreliable at best.

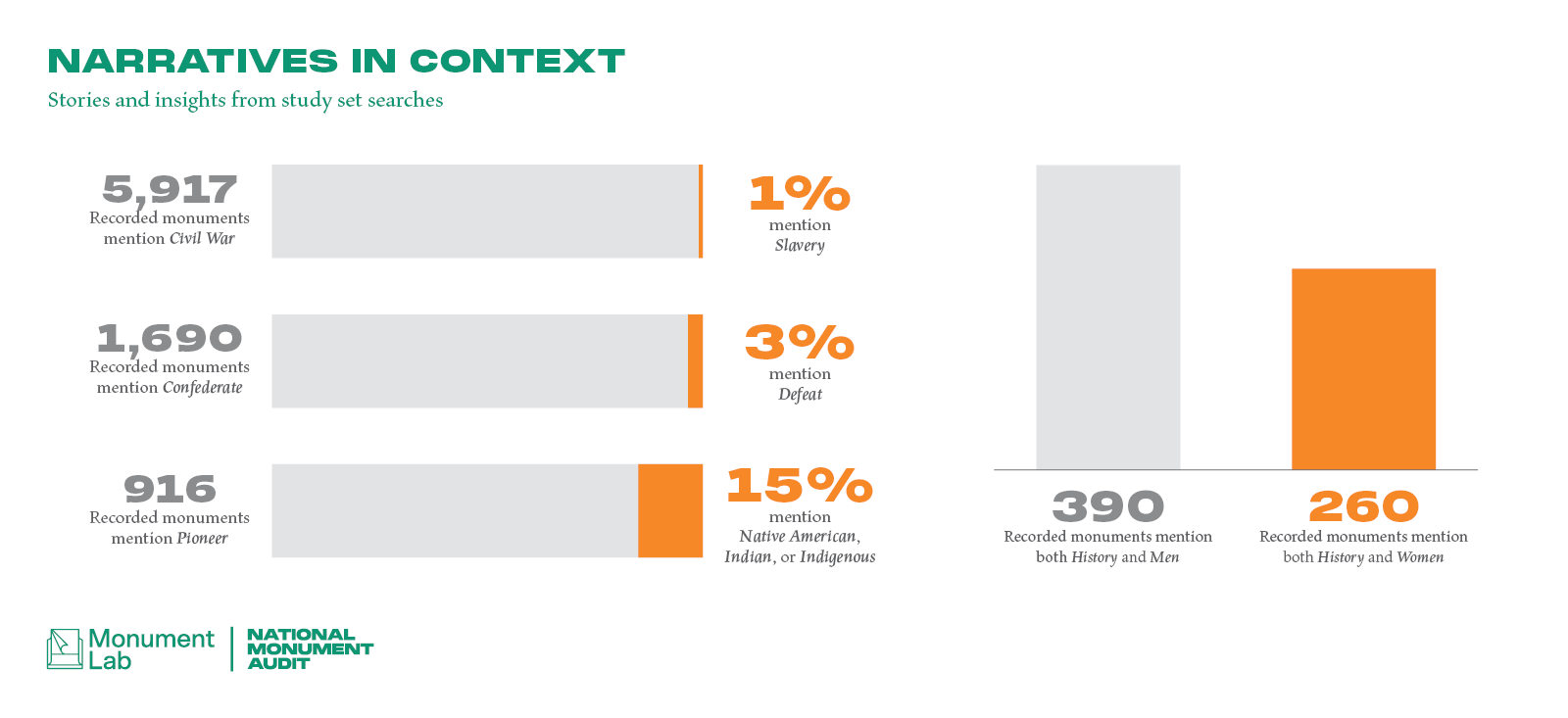

Specific types of monuments are constructed within particular political, social, and cultural contexts. For instance, the biggest surges of Confederate monuments were dedicated between 1900 and 1920, along with the rise of Jim Crow and a second wave of symbols that marked the resistance to the gains of the civil rights era in the latter half of the twentieth century.11 Similar to the way that the construction of Confederate monuments was used to exert power over Black Americans in the early twentieth century, statues devoted to a mythologized story of white Western expansion were created in the mid-twentieth century.

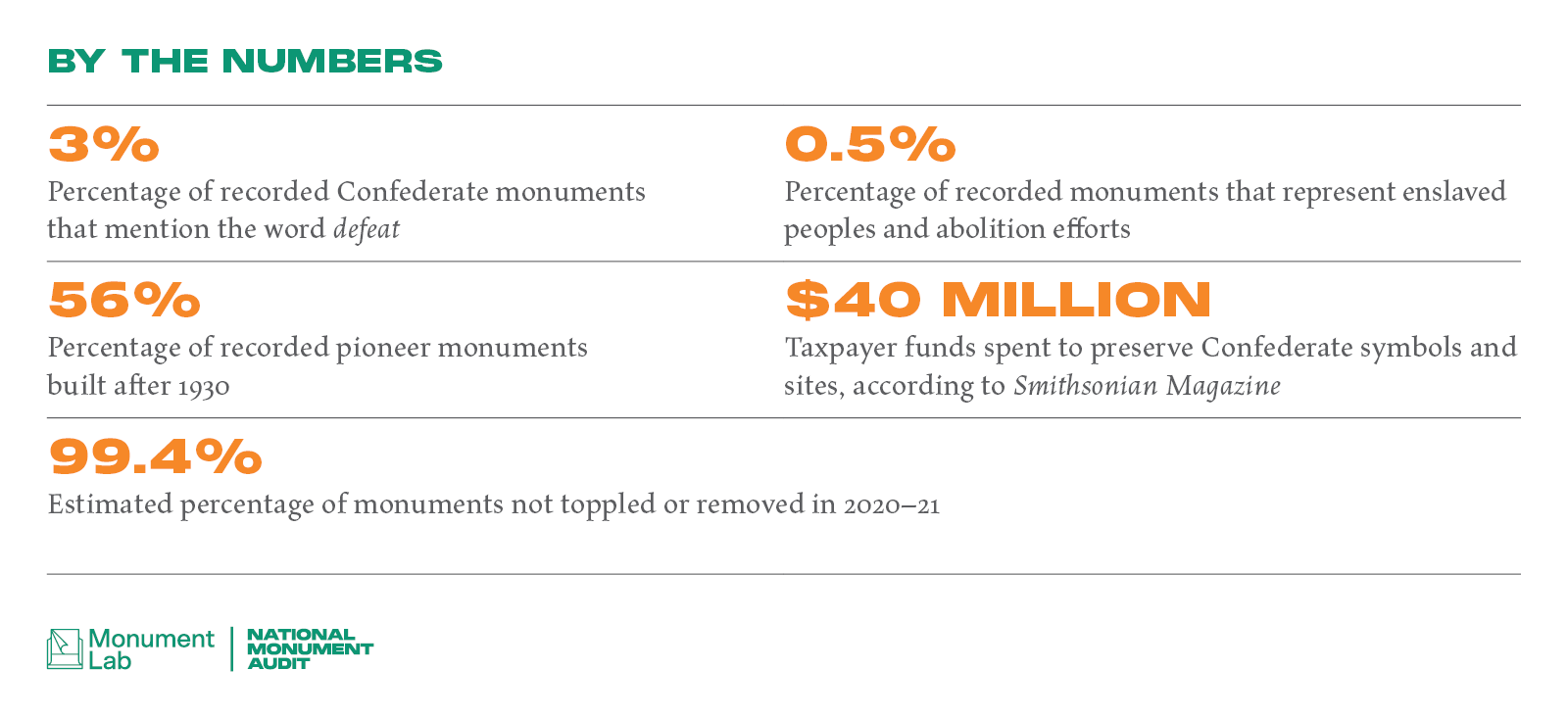

Over half (56%) of the results for the search term pioneer in our data set were built after 1930, as part of a popular culture's myth-making around the frontier and “Wild West,” while diminishing the forcible removal of many Indigenous communities from their homelands through armed conflict and land dispossession.

Traditionally, monuments obscure the particular circumstances and motivations behind their own creation. They are presented as timeless and universal.

While monuments are not history, they can and should be held accountable to history. Monuments that perpetuate harmful myths and that portray conquest and oppression as acts of valor require honest reckoning, conceptual dismantling, and active repair.

CALL TO ACTION

Engage in a holistic reckoning with monumental erasures and lies and move toward a monument landscape that acknowledges a fuller history of this country.