Laurel V. McLaughlin (LM): In my previous contribution to Monument Lab’s Bulletin, entitled, “As Strangers and Refugees: Olu Oguibe’s Performing Monument,” I attempted to qualify the dialectical “aftermath” that modulated the meaning of Oguibe’s monument Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument (Monument for Strangers and Refugees), 2017.1 I was interested in the performativity of the seemingly static and centralized obelisk in the circular Königsplatz of Kassel inscribed with Jesus’ words from the Gospel of Matthew, “I was a stranger and you took me in” in German, English, Arabic, and Turkish.2 The monument gradually bore the shifting political dialectics entangled in the so-called “European Migrant Crisis,” as pressure from the AfD (Alternative for Germany), amongst other far right-wing organizations, called for its removal. The city of Kassel caved to such nativist calls, and disassembled the work into pieces, stored offsite in an undisclosed government facility.3 Shortly after I wrote the article, Olu Oguibe and I discussed the aftermath of the work and its continued performativity within political imaginaries. In this discussion, he mentioned an artist, Pamela Valfer, who wanted to work with the monument in its dismembered form. I was intrigued to learn if Valfer’s work would be an extension of the political performance, and if so, in what direction. The following conversation unfolded during Pamela Valfer’s conceptualization and installation of her work, In Situ: A Monument to a Monument—“Monument to Strangers and Refugees” Olu Oguibe.

Dismantled Installation View of Olu Oguibe, Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument (Monument for strangers and refugees, 2017), Concrete, 3 × 3 × 16.3 m. Photo: Pamela Valfer.

Pamela Valfer, In Situ: Monument to a Monument, 2019 Frottage drawing (set 1 of 4) Turkish, Lithographic crayon on Fabriano paper, 150 x 169 mm. Photo: Pamela Valfer.

Laurel V. McLaughlin (LM): Oguibe generously put us in contact following conversations about his work, Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument (Monument for Strangers and Refugees). Let’s begin by reflecting on your connection with Oguibe, and then our own connection. These encounters strike me as continued performances within a web of interconnected political intentionalities. So, do you see Oguibe’s monument as structuring your research process for this installation? And then, do you consider this as a kind of collaboration with Oguibe?

Pamela Valfer (PV): I became familiar with the shifting situation around Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument (Monument for Strangers and Refugees) while attending Saas-Fee Summer Institute, 2018 in Berlin. Olu came and spoke at the Institute about his work and, in particular the obelisk piece. At the time, the work had just been taken down by the city of Kassel. It’s future was in flux. Initially, I was struck by the seemingly simple gesture of Olu’s obelisk, how a quote from the Bible, in solemn form, could have stirred such a backlash of nativist response.

While the work actively operates within a contemporary political sphere it also has a potency linking the past to the present in a quiet manner. The work speaks to both the history of Kassel, Germany’s history of “othering” as a whole, and the current parallels to the obelisk’s immediate unfolding history. To me, it seemed timeless. Being a part of the Jewish American diaspora I felt connected yet culpable. My family has history of displacement in Europe and Germany in WWII, so this felt eerily familiar.

In my own practice, I am interested in historical events that are linked, either directly or indirectly, to a cycle of repetition. I am critical of cultural political agendas that surreptitiously inhabit our lives, in particular, the illusion of autonomy within these platforms. I was therefore naturally drawn to the complexity of Olu’s piece and the symbiotic relationship it had to Germany’s history as well as our global present.

Therefore, the obelisk took on both form and function for me. It’s function acted to uncover the actual mechanism that the gesture was critiquing. It acted out its own part of history within history. So, collaboration for me was with the performance, the stage of events that unfolded around the obelisk, not just the form. With my intervention, the memorial had an opportunity to continue to function in this different transformed way, unmoored from its original location but still imbued with its unfolding history.

LM: Could you describe In Situ: A Monument to a Monument—“Monument to Strangers and Refugees” Olu Oguibe—your process for the work and its relationship to Berlin?

PV: My project ultimately is a memorial to the fallen obelisk. I wanted to capture the obelisk in this loaded moment, while it was stored in the Kassel city storage facility, hidden, in the mud, in pieces. The work was in a state of brokenness and flux, a new form that mirrored the meaning but in a totally unplanned way by Olu. Drawing mixed with installation became my methodology to explore this indeterminate state.

For the drawings, I chose to use the process of rubbing (frottage) for the mark making. The rubbings were done on each side of the obelisk, capturing the engraved text in German, English, Arabic, and Turkish. Using the frottage technique, for me, conveys a sense of memorial and as the obelisk was displaced, in-situ. I spent a week meditatively making the rubbings, it was a solemn activity, and it was very personal.

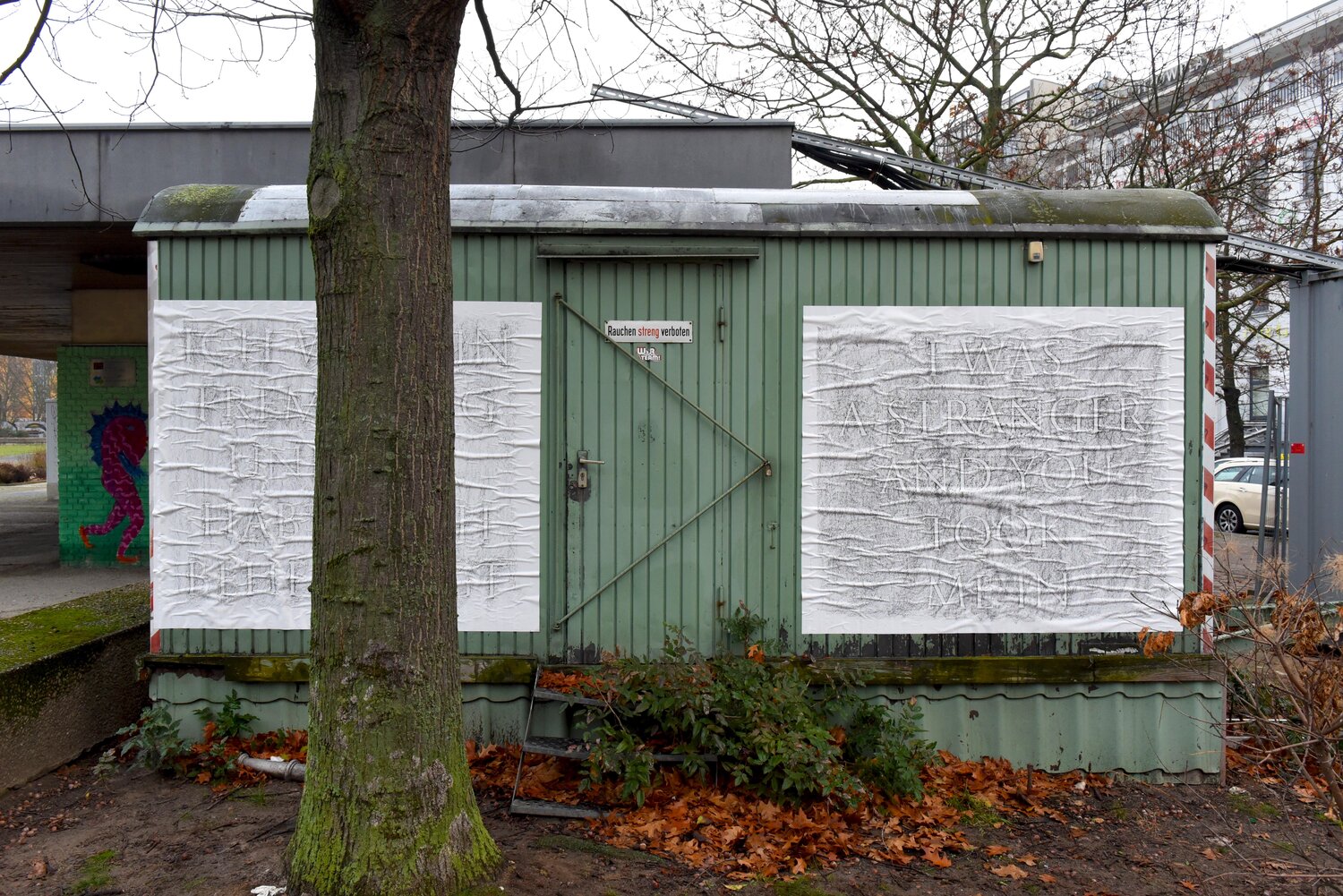

The second half of the project was to install the drawings in Germany, in particular Berlin, a locale that spoke to the dark history of anti-immigrant policy and the “othering” of humanity. I chose Berlin as my initial site due to its aura of political power and collective trauma of history. My gesture to conflate the AfD’s actions, to other locales in Berlin of similar ethos, was to integrate the past to the present. I also thought it important that the gesture be made from a descendant of the last expelled group from Germany, the diasporatic Jew, a stark reminder of the on going cycle.

I recently completed the installation of drawings at four locations around Berlin. The locations include:

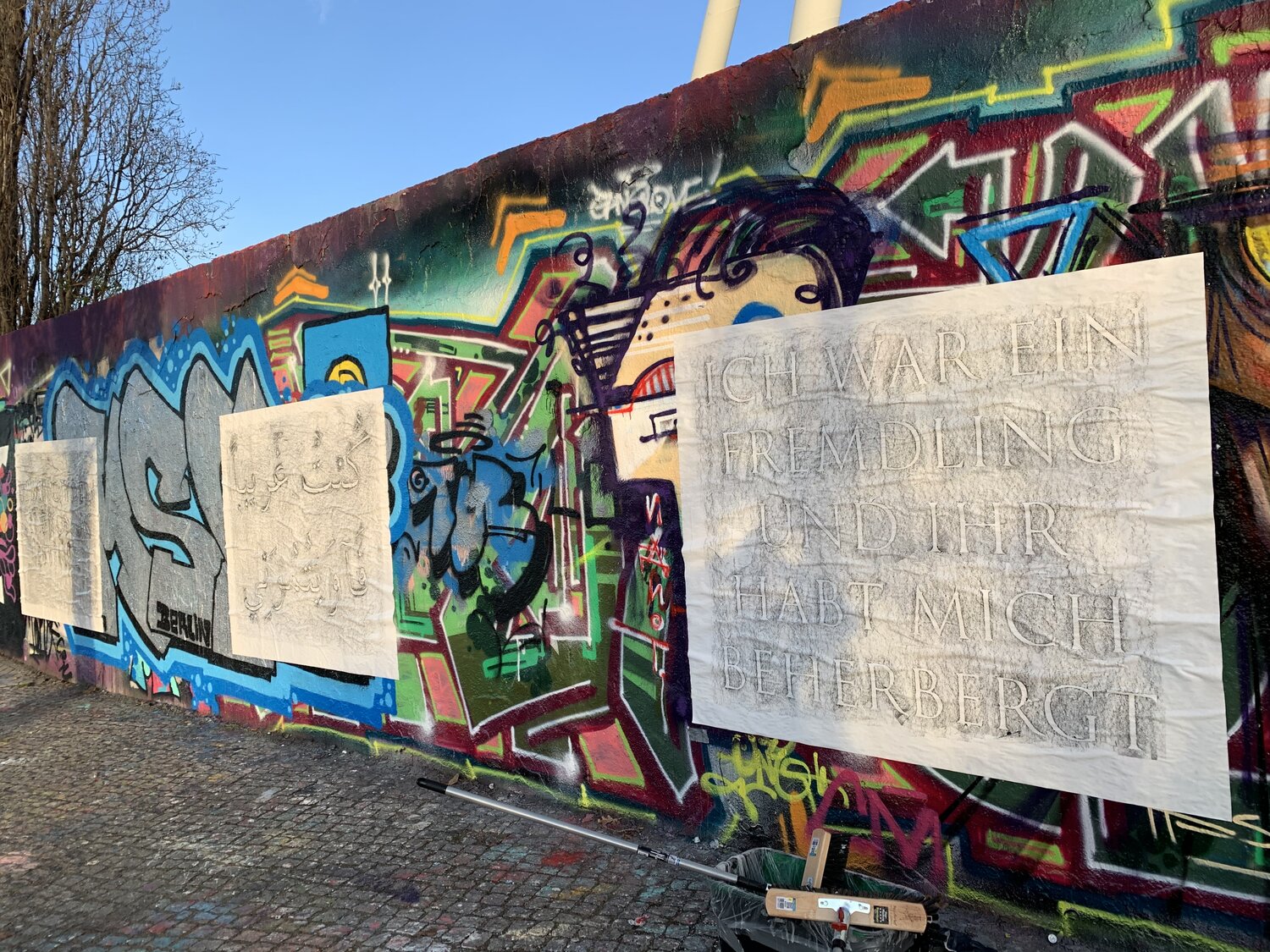

Site 1: GPS: 52.543431, 13.403658; Mauerpark Gleimviertel, 10437 Berlin, Germany. [The name translates to “Wall Park,” referring to its status as a former part of the Berlin Wall and its “Death Strip.” There were in fact two walls: a 20-foot inner wall, on the West Berlin side, and a shorter back wall. Between them was a militarized strip of land with anti-tank iron barricades, colloquially known as “Czech hedgehogs,” beds of nails, electrified fences, and guard towers with armed guards who would, and did, shoot; over one hundred attempted escapees were killed while fleeing by the time the Wall came down in 1989. This space between the walls was called the Death Strip.] Photo: Pamela Valfer.

Site 2: GPS: 52.501767, 13.342663; Wittenbergplatz Station (Berlin U-Bahn lines U1, U2 and U3) 10789 Berlin, Germany. [This is a station from which trains departed for concentration camps. In front of the station there is a metal plaque that holds 12 slats bearing the names of those concentration camps. The words on top read, “Orle des Shreckens, die wir niemals vergessen dürfen” [Places of Horror Which We Are Never Allowed to Forget.” ] Photo: Sean Smuda.

Site 3: GPS: 52.504026, 13.346554; AfD Alternative für Deutschland office Kurfürstenstraße 79, Berlin, Germany. Photo: Sean Smuda.

Site 4: GPS: 52.504762,13.352593; Lützowplatz park across the street from AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) office. [Schillstrasse 9, GPS: 52.504221, 13.350709 Schillstrasse 9, Alternative für Deutschland, office, Federal and state offices. Both facilities are located in office space at Schillstrasse 9, Berlin, Germany on Lützowplatz.] Photo: Sean Smuda.

LM: You mentioned the bureaucratic red tape. Oguibe’s monument for documenta 14 found itself torn between political ideologies, especially in its dismantled state. This condition, in some ways, acts as a kind of performative parallel for migrants, refugees, and those that find themselves displaced by political upheaval, border ideologies, and configurations of the nation state. How did you gain access to the restricted work and realize these frottage drawings? Did this endeavor at all relate to the ways in which histories converge in your project?

PV: Bureaucratic red tape was a new experience for me. I did find it interesting how the obelisk ended up mirroring the complex political system for which it was critiquing and I was aware of this irony from the start… It was what drew me to the project.

In terms of realizing the project, it was always to start with the artist. Once I received Olu’s support, there was a process of negotiating with his representative gallery and then finally requesting access to the obelisk from the city of Kassel. Each system demanded a slightly different touch.

LM: I’m reminded of the concept of the ruin in looking at your drawings, with the way that they reference Oguibe’s monument and the city of Berlin. As you said, you made frottage impressions from the remains of Oguibe’s monument and you intended for the residue in turn to call attention to the ethical state of the city, from what I understand. Andreas Huyssen notably wrote about the power of ruins, citing nostalgia and their connections to modernity.4 He also noted the seemingly counter impulse towards erasure: “Not surprisingly, then, the major concern in developing and rebuilding key sites in the heart of Berlin seems to be with image rather than use, attractiveness for tourists and official visitors rather than heterogeneous living spaces for Berlin’s inhabitants, erasure of memory rather than its imaginative preservation.”5 In the context of migration, the ephemerality of transit often obscures ruins; and what’s more, governments are keen to erase even the traces of migrant presence. But Oguibe’s work seemed to solidify a kind of critical nostalgia, and your works played on this ruined permanence by reinserting their place within the landscape. Could you talk more about how you see ruin and erasure functioning in your work?

PV: This question brings to mind an interesting chapter from Hito Steyerl’s book Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War.6 Chapter two explores the cycle and symbiotic relationship between capitalism and war.7 Hito discusses how war is the engine of capitalism as the cyclical ruin is constant and never ending. War wipes away history while capitalism is there to ensure the follow-up reconstruction and white-washing. I think that the preservation of ruins is also a complicated subject as meanings are not fixed—culture moves forward, things change, trauma disappears into the fog of time. Auschwitz is meant to stand as a stark reminder of the atrocities of fascist rule and the scapegoating of people that led to the Holocaust. Now people take selfies in the camp and people picnic on the Holocaust Memorial; so there is erasure happening on many different levels all the time. I am operating in the liminal space, in both the ruin and the cleaned-up building holding the dark history just underneath.

Pamela Valfer, In Situ: Monument to a Monument, 2019. Footage: Cilian Woywod and Marcos Brias.

LM: “Operating in the liminal space” seems necessary here, especially in light of the ruin and the impermanence of your monument. How do you see the impermanence (which is seemingly paradoxical to most conceptions of a monument) being a critical factor in your otherwise site-specific installation?

PV: The idea was that the work would fall apart, disintegrate, or be removed by outside forces. This—the final act—would mirror the journey of the obelisk’s deconstruction. It was imperative that it should be the original drawings that were installed, as the project was never intended to be commodified. Thus, it was both a warning as well as a personal offering. The final drawings installed, puckered like skin, and doomed for erasure seemed to encapsulate the totality of the past and present.

LM: As the obelisk for Königsplatz responded to and depended upon the histories embedded within its specific site concerning migration history. How do your drawings interact with the German historical landscape as you’ve installed them throughout Berlin? And also, how did you install these works—clandestinely?

PV: My goal was to connect the history of forced migration in Germany to the present situation (in all its dark corners), and I feel the current controversy with the AfD and the obelisk is a strong contact point. I am definitely thinking a lot about the political tenor of Europe and America at the moment. The difficulty in proceeding with the project was to find the delicate balance between sensationalism and restraint. At the moment, I see there must be a scaffolding of both approaches, one built upon the other. There may be obvious choices and there may be obtuse juxtapositions but I see all strategies as equally interdependent.

The notion of anonymity is tough. The installation required finesse, expertise, planning, and research and the advice from a lot of street artists from both Los Angeles and Berlin. Anonymity, long term, is more difficult, especially as the scope expands. Yes, this leaves me open to risk, but I have made the choice to open the door for dialogue. I believe standing on the sidelines during these critical times is not an option and part of the layers of the work needs the implication of myself, my own history.

LM: This project has been one defined by research as you’re engaging public art, collective histories, and personal familial history. Could you describe your research process thus far and perhaps detail upcoming steps?

PV: My process is both intuitive and academic. After spending a little under a year getting permission, I then went to Kassel and executed the drawings, later returned to Berlin to do research and site visits (sometimes undercover). I located five potential sites, always knowing as things unfolded, due to safety or my own artistic interests, that things might change. I am happy with the outcome, and I can take this planning experience to future installs. I would like to continue the project in different locales both locally and globally. As mentioned above, I have a limited set of drawings, and it is my intention to hang them all, once they are gone the project will be completed.

LM: Do you have other sites in mind? And will these installations continue to engage Oguibe’s obelisk and your familial history?

PV: I do… I am currently researching other sites and critiquing the importance of my presence in the work as it continues. My presence was important for the work in Germany, outside of that context I am not sure. The work is constantly evolving, dependent on the intersection of locale and the obelisk’s performative history. There are many places, too many in fact, that have dark corners, the juxtapositions are endless. I look forward to being a part of the history of the obelisk, as well as allowing it to evolve into new dialectics.

Pamela Valfer creating frottage drawings for In Situ: Monument to a Monument, 2019. Photo: Cilian Woywod.